Theater Troupe vs. Army

“There is no means of testing which decision is better, because there is no basis for comparison. We live everything as it comes, without warning, like an actor going on cold.”

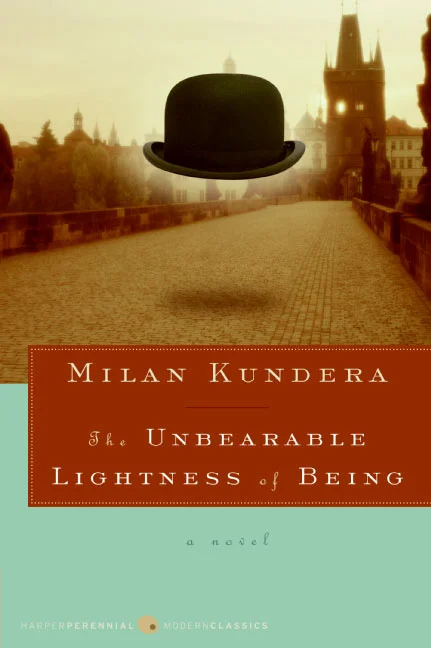

Milan Kundera’s novel The Unbearable Lightness of Being explores the idea that each of us can choose only one of the many possible paths for our lives. Since we only get to live our lives once, we do not know what our lives might have been had we chosen otherwise. We only know what our lives are now as a result of the choices we really have made. The main characters in the book are Tomas, a philandering doctor, and his wife Tereza, a sensitive bibliophile and photographer who is utterly devoted to him. The two of them meet through a series of unlikely coincidences, and one of the central choices in the novel is Tomas’ choice to marry Tereza, a decision that heavily altered the course of his life.

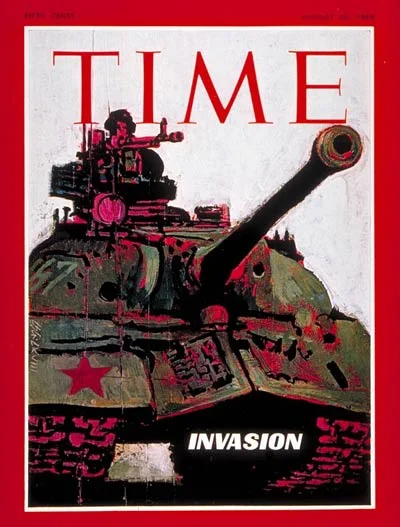

Tomas’ and Tereza’s relationship is played out against the events of 1968 in Prague, so the Soviet invasion in August of that year and the subsequent reestablishment of the Communist regime play heavily into the plot. In particular, the regime’s restriction on freedom of expression is an important part of the story since early on in the book Tomas writes an article for a Czech paper condemning Czech communists.

1968 Cover of Time Magazine

Fearing recrimination for the article he wrote, Tomas, along with Tereza, flees to Switzerland, where Sabine (Tomas’ longtime mistress) is already living. Tomas is happy enough in Zurich, but Tereza struggles to find meaningful work. Tereza is also acutely aware of the fact that Tomas continues having affairs with multiple women, including Sabine.

Feeling that she is a burden to Tomas, Tereza makes the decision to move back to Prague without telling him. It is a strange decision since her devotion to him is absolute, but it makes sense when seen in the context of her fear that she is ruining his life. Tereza tells herself that “in spite of their love, they had made each other’s life a hell." What she doesn’t know as she is making this decision is that as soon as Franz discovers she has left Zurich for Prague, he will leave to go be with her. And, of course, once he is back in Prague, he will be faced with the consequences of what he wrote about Czech communists.

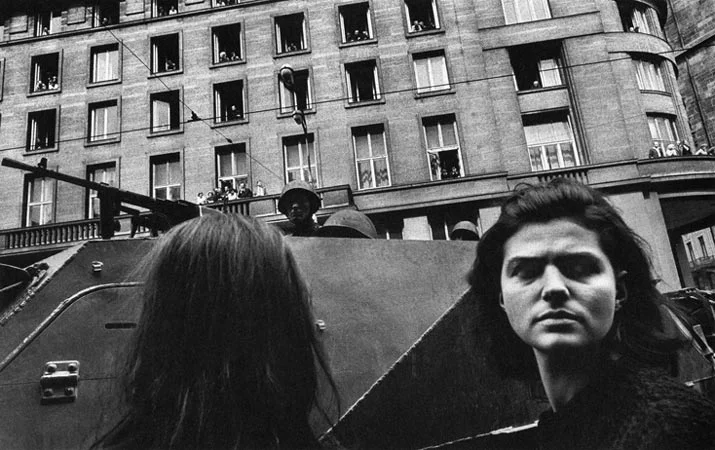

Josef Koudelka, Prague, August, 1968, Digital Inkjet Print

In a book where the choice to do one thing instead of another is a central theme, this choice stands out as one of the most consequential. Once in Prague, Tomas faces pressure to denounce his anti-communist article. He refuses, loses his position as a doctor, and becomes a window washer instead. Still, even after all of this, it is not the end of his being pressured to sign documents others have written. Soon an editor of an underground paper approaches him about signing a petition for the amnesty of political prisoners. Tomas, however, feels that he is being manipulated once again, just by a different group of people, and refuses to sign.

Meanwhile, Franz, an unhappily married intellectual from Geneva, falls in love with Sabine, and the two of them travel together whenever he has to lecture in a foreign city. Temperamentally similar to the ever-committed Tereza, Franz cannot tolerate being with two women at the same time, and ultimately leaves his wife for Sabine. Unfortunately, Sabine hates to commit and she leaves Franz when she realizes he wants to marry her.

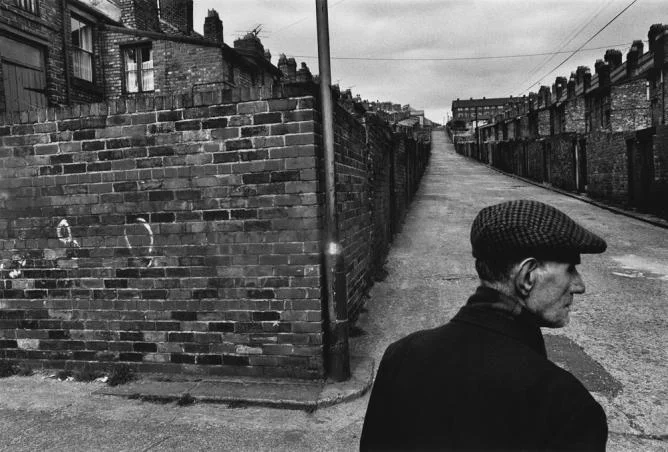

Josef Koudelka, From Exiles - Revised and Expanded Edition,

Though Franz finds another lover, he never fully recovers from the loss of Sabine, and many of his later decisions are influenced by his enduring attachment to her. When he receives word from a colleague of a plan to march on Cambodia and demand permission to enter the country with medicine and food, he thinks of what Sabine might have wanted. Remembering that she was a refugee from another country occupied by its neighbor’s Communist army, he imagines she would want him to march on Cambodia, and he agrees to participate.

From time to time Kundera breaks from the narrative and interjects his own authorial thoughts about the situations his characters find themselves in. In analyzing Franz’ decision to march in Cambodia, he makes a comparison to the editor in Prague who encouraged Tomas to sign the petition.

“I can’t help thinking about the editor in Prague who organized the petition for the amnesty of political prisoners. He knew perfectly well that his petition would not help the prisoners. His true goal was not to free the prisoners; it was to show that people without fear still exist. That, too, was playacting. But he had no other possibility. His choice was not between playacting and action. His choice was between playacting and no action at all. There are situations in which people are condemned to playact. Their struggle with mute power (the mute power across the river, a police transmogrified into mute microphones in the wall) is the struggle of a theater company that has attacked an army.”

A theater company cannot, at least not with brute force, defeat an army. And yet, when faced with the choice between doing nothing and playacting, playacting becomes a more appealing option. Writing a letter which will not have its desired effect, acting out a drama which will not bring about change, signing a petition whose goals will not be achieved, or doing absolutely nothing – these are the sorts of choices people living under repressive regimes have to choose among.

The characters in this book are continually making choices. Whether it is signing a marriage certificate, a petition, or a letter to the editor, the question is always, “Is it worth it?” Will the outcome of signing be better than the outcome of not signing? And along with these questions is the ever-present question of, “How can we know that we chose well since we will never know what else might have been?” If Tomas had never met Tereza, he might have had a successful career as a doctor in Zurich. Would this outcome have been better than the life he lived by her side?

At the end of the book, this question is still not fully resolved, but the fact of the book’s existence points toward an answer. After all, Milan Kundera wrote the book. You cannot write a book without believing in the power of words and in the power of creating things. Perhaps there are times when artists, writers, and actors look like theater troupes waging war on real armies. Perhaps the choice to commit to something, whether it is a movement or a person, appears ineffectual. Perhaps we’ll never know with utter certainty whether the choices we make and the things we create are the right ones and whether they are better than the choices and things we didn’t make. Nevertheless, like Kundera himself, we do choose to make things. We do choose to commit to people and ideas. The very fact that oppressive regimes forbid these things is evidence of their power, so we continue, often in the face of uncertainty, with the work we have chosen.

Josef Koudelka, Bohemia, 1967, Gelatin Silver Print

Note: All the photos in this post are by Czech photographer Josef Koudelka. Koudelka captured many powerful images in Prague during the same period that Kundera wrote about. I have included these photos of real people, since they fit with the general tenor of Kundera's fictional novel.