Amsterdammers

Russell Shorto’s Amsterdam: A History of the World’s Most Liberal City traces the city’s liberalism from the twelfth century when a handful of industrious farmers began piling up dirt to hold back the sea through the miracle in 1345 that made Amsterdam a destination for devout pilgrims, the Protestant Reformation and beginning of religious freedom, the golden age in the 17th century, the horrors of WWII, and the peace-loving, provocative youth culture of the 1960’s that reestablished Amsterdam’s reputation as the center of liberalism.

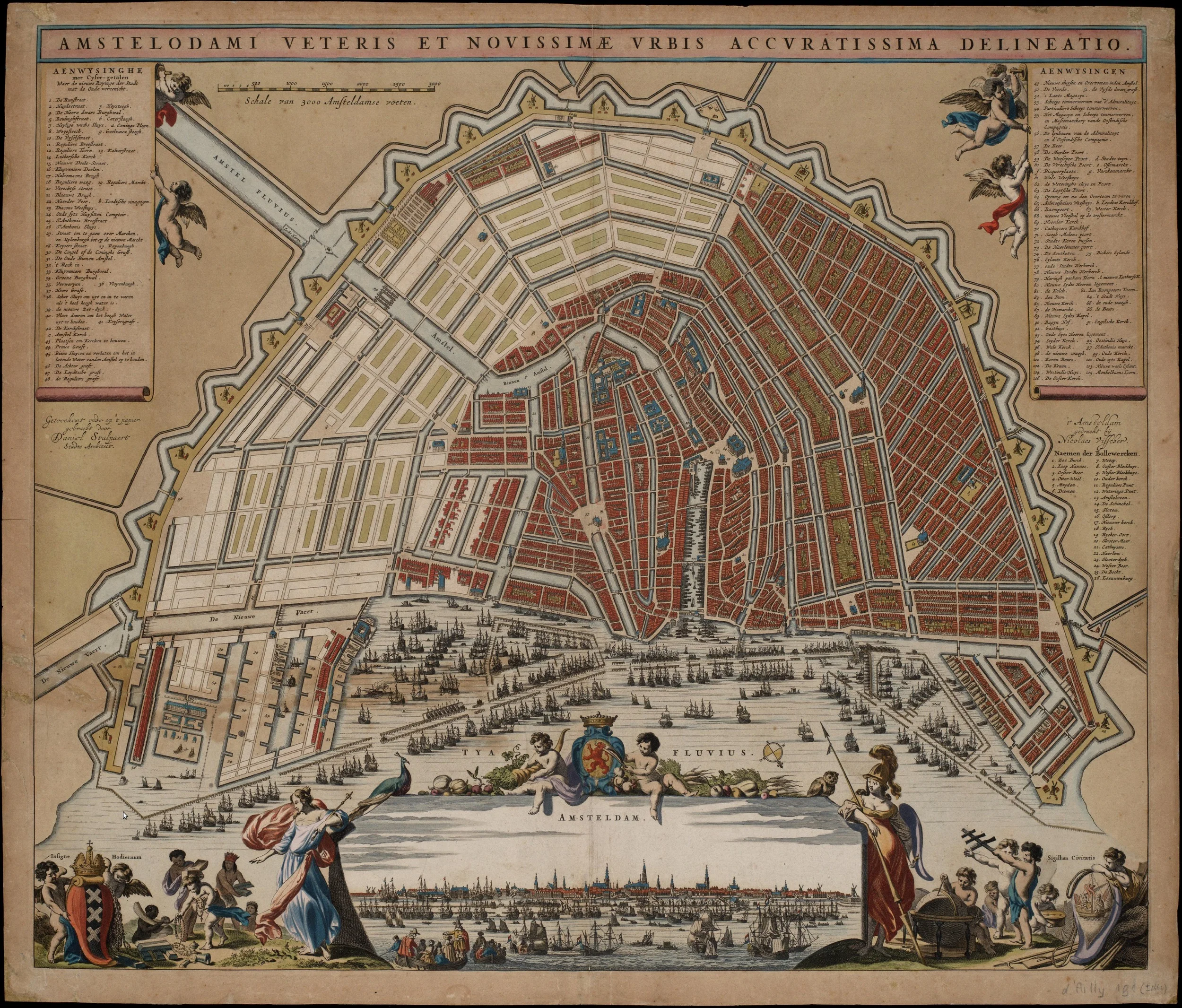

One of Shorto’s main arguments is that the way the canals and solid land were sculpted out of the once-soggy lowlands, a process requiring both autonomy for individuals (who bought the plots of land) and collaboration within the community (which had to build dikes and dams, operate windmills, and dig canals) is key to understanding Amsterdam’s particular brand of liberalism today. During the Middle Ages in other parts of Europe the lord of a manor oversaw the peasants working on his estate; in Amsterdam neither the church nor the nobility owned all the land. Each small plot of earth was reclaimed from the sea by the ingenuity and hard work of the community and then purchased and farmed by the individuals living there. This meant Dutch peasants had no need to adopt an attitude of deferential obedience since they were their own bosses. What they did need to adopt, however, was an attitude of tolerance and cooperation toward their fellow peasants. And, once the city became a center of global trade, they extended this attitude of tolerance toward other types of cultural difference as well.

A map of Amsterdam with its canals from 1662

A canal in modern Amsterdam

While the argument is impossible to prove, it does (to use an idiom appropriate to the marshy lowlands) seem to hold water, and as I read Shorto’s book I became convinced that the unique landscape of the Netherlands played a role in its becoming a place that values both individualism and tolerance for otherness.

As an artist, I’m particularly interested in how the culture of Amsterdam shaped the types of art created there. One of the best-known artists of Amsterdam is Rembrandt van Rijn, who frequently inserted his own visage into his paintings and etchings of Biblical scenes. He also painted some of the most probing and psychologically sophisticated self-portraits any artist has ever made.

Rembrandt van Rijn, Self-Portrait with Beret and Turned-Up Collar, 1659, Oil on canvas

Shorto contrasts Rembrandt’s work with that of earlier artists, particularly Catholic artists working in Italy. He shows that Rembrandt's work was different, in part, because of the individualism and freedom that came with being an Amsterdammer.

“He developed a dexterity with what were called historical paintings. We would call them religious paintings (though some were of mythological rather than biblical subjects), but they were fundamentally different from those of Michelangelo, Raphael, and other earlier artists. Those artists were commissioned by churches and their work was installed behind altars: the artists were workers in the business, the industry, of religion. But these were different times, and this was a different place. The Dutch provinces had broken free of Catholicism and were on a new trajectory, in the service of individuals, which encouraged them in turn to be interested in individuality: their own and that of their subjects. The clients of Dutch artists were not priests and popes but herring wholesalers and flax merchants.”

In the past I’ve often thought about the emotional complexity of Rembrandt’s work, but I had never considered that this emphasis on the interior life of his subjects, including the subject of himself, was partly a product of the culture of Amsterdam. This tendency toward self-examination is particularly apparent in a painting Rembrandt made as a young man, not even twenty years old: his Stoning of Saint Stephen. Shorto points out that Rembrandt included not just one but three self-portraits in this work, since Rembrandt’s face appears on three figures: a saint, the saint’s tormentor, and a figure in between the two of them who stares out at the viewer. Shorto expresses the dynamic between these three representations of Rembrandt well:

“What was going on here? From our psychological perspective, we might say the artist was making a statement or inquiry about himself, the sort of thing that most people at the threshold of adulthood do. He was wondering who he was. Am I a saint or a guilty sinner? Am I someone who violently refutes the manifestation of God’s grandeur? The third painted self, in the traditional stance of staring out at the viewer, which is tucked precisely in between the other two, seems to be posing this quandary, asking the viewer to help him figure himself out. If this is true, then the artist was doing something that is commonplace now but had rarely been done before: using his art for his own emotional needs.”

Rembrandt van Rijn, The Stoning of Saint Stephen, 1625, Oil on canvas

The idea that art can be used in a therapeutic process of self-examination is popular today, so popular it is easy to forget it was ever new. When I’ve asked students why they believe people make art today, one of the most common answers given is self-expression (or some variation of that phrase). We take for granted today the idea that the psyche of the artist is in some way on display when he exhibits his work, and we rarely consider the history of that idea.

Shorto only mentions Vincent Van Gogh briefly in his book, but the parallels between Van Gogh and Rembrandt are hard to ignore: both were prolific painters of the self, both were Dutch, and both were able to pierce through the mere appearance of people and capture their inner life. Van Gogh only lived in Amsterdam for one year, and it was during a period in his life when he was studying for the ministry (something he failed at miserably), not seeking to become an artist, but it is nevertheless possible that he absorbed something of the city’s culture during that short time.

Vincent Van Gogh, Self-Portrait with Straw Hat, 1887, Oil on cardboard

Two quotes from Van Gogh stand out to me as representing both the individualism and attitude toward community that Shorto claims underlie the liberalism of Amsterdam. On one hand, Van Gogh wrote, “An artist needn’t be a clergymen or a churchwarden, but he certainly must have a warm heart for his fellow men.” On the other, Van Gogh also wrote, “I put my heart and my soul into my work, and have lost my mind in the process.” Van Gogh simultaneously reached out to the world around him and also made his own emotional life the subject of his work. He showed acceptance for others in whatever state he found them even as he valiantly sought to express himself as an individual. In that sense, his work embodies what it means to be an Amsterdammer.

Vincent Van Gogh, The Potato Eaters, 1885, Oil on canvas